2014

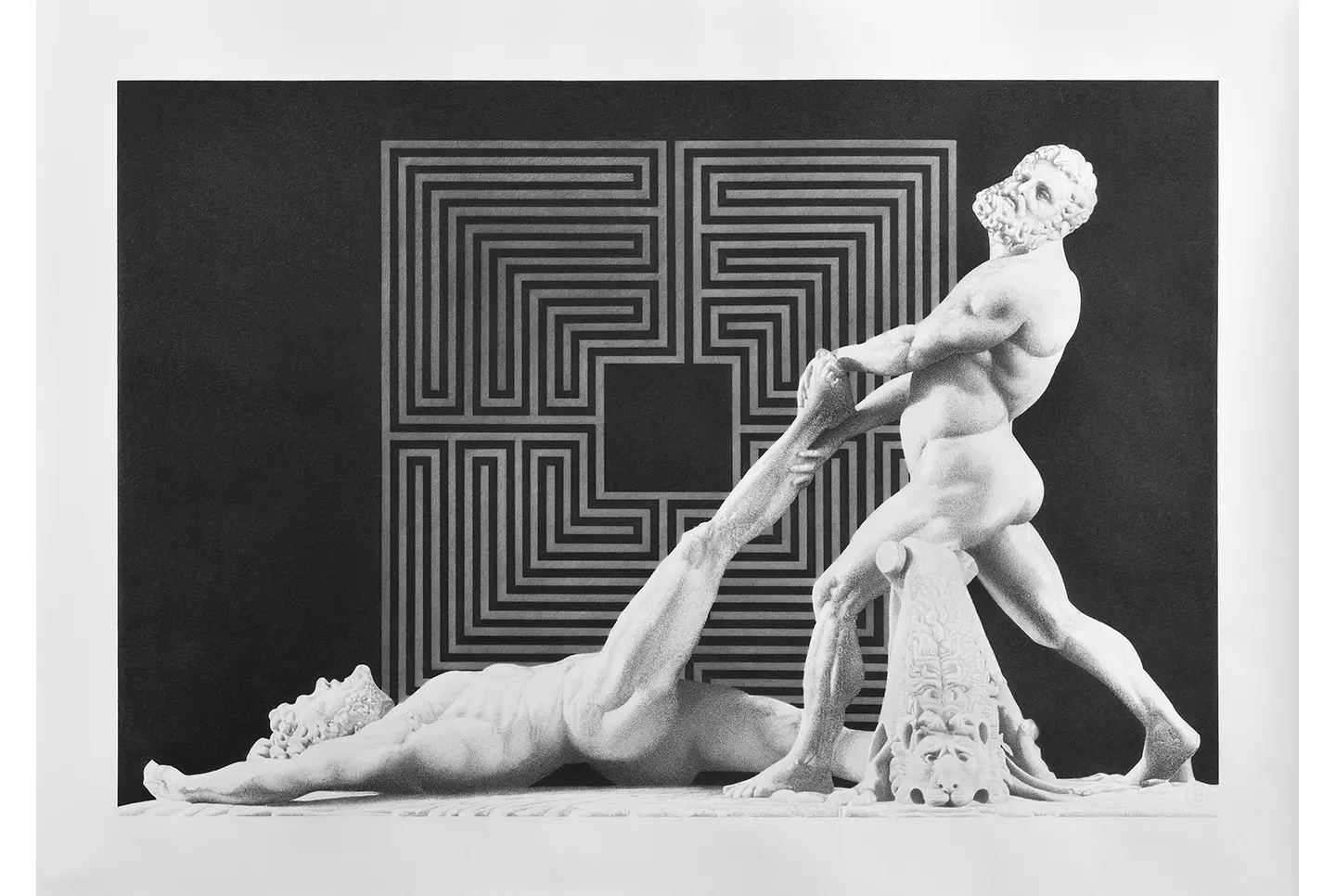

L’Art du combat / Galerie Tarasieve Paris

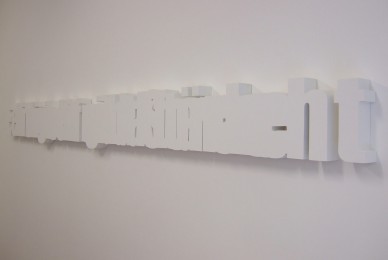

The Art of Combat The Exhibition as Chessboard – Anaël Pigeat

Jean Bedez plays chess, but this is the first time he has transformed an exhibition into one giant chessboard, on the scale and in the time of the gallery−or rather, in several time frames: the time needed to make the drawings, the time of the narratives contained in the images, and the time needed to look at them in the exhibition. This is titled L’Art du combat, from the French title of The Chess Struggle in Practice, a book by the Soviet grand master David Bronstein (L’Art du combat aux échecs).

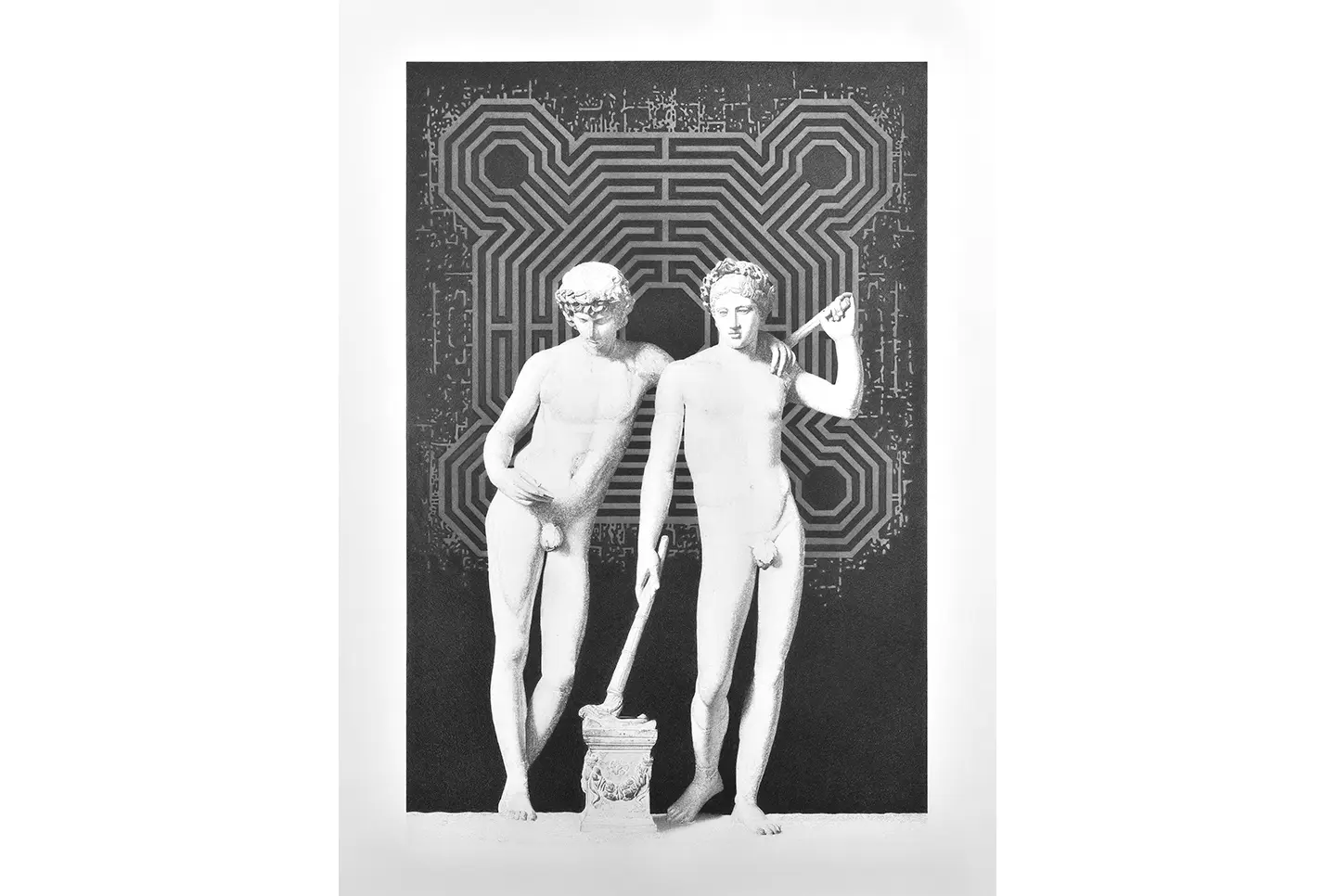

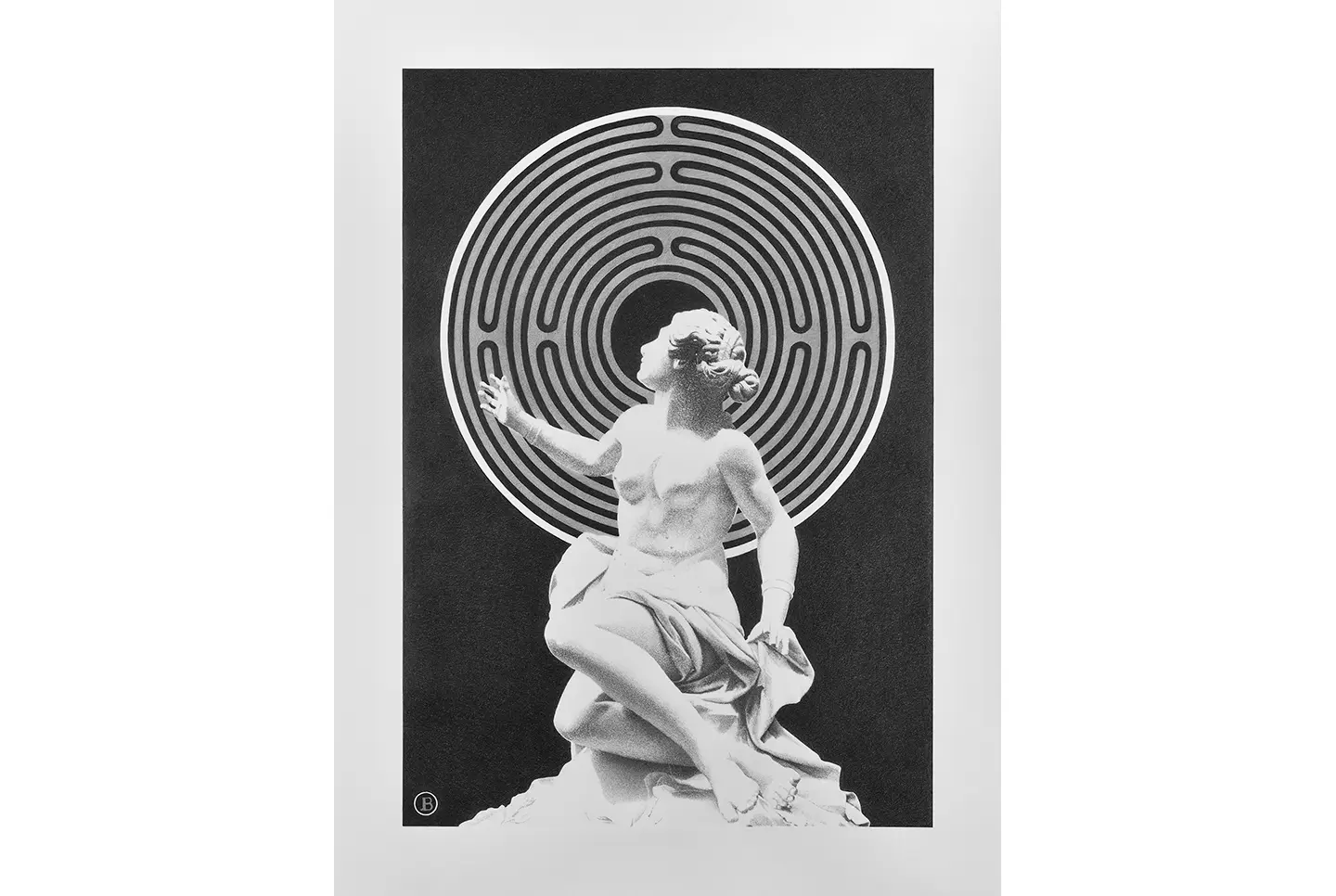

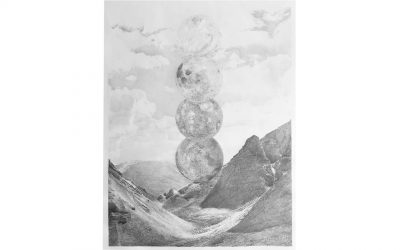

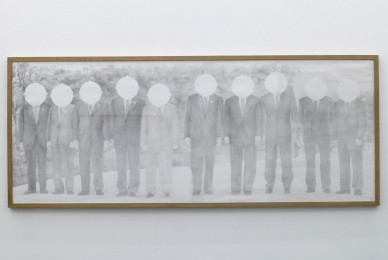

The “opening” (in the chess player’s sense of the term) that greets visitors entering the exhibition consists of three small-format drawings, each representing the same two players, face to face, in three frozen, suspenseful moments. This is the first chess world championship held after World War II, pitting the United States and Soviet Union against each other in Zurich at the height of the Cold War in 1953. That is what Bronstein describes in his book. His victory began a twenty-period of Soviet chess triumphs at the highest level. And that is what Bedez shows us, except that in each image the chessboard is replaced by a glowing nimbus of light, whereby he directs our attention to the drawing, and to the immemorial time alluded to by this historical situation.

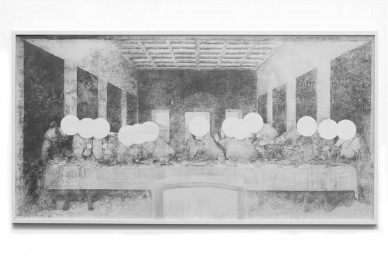

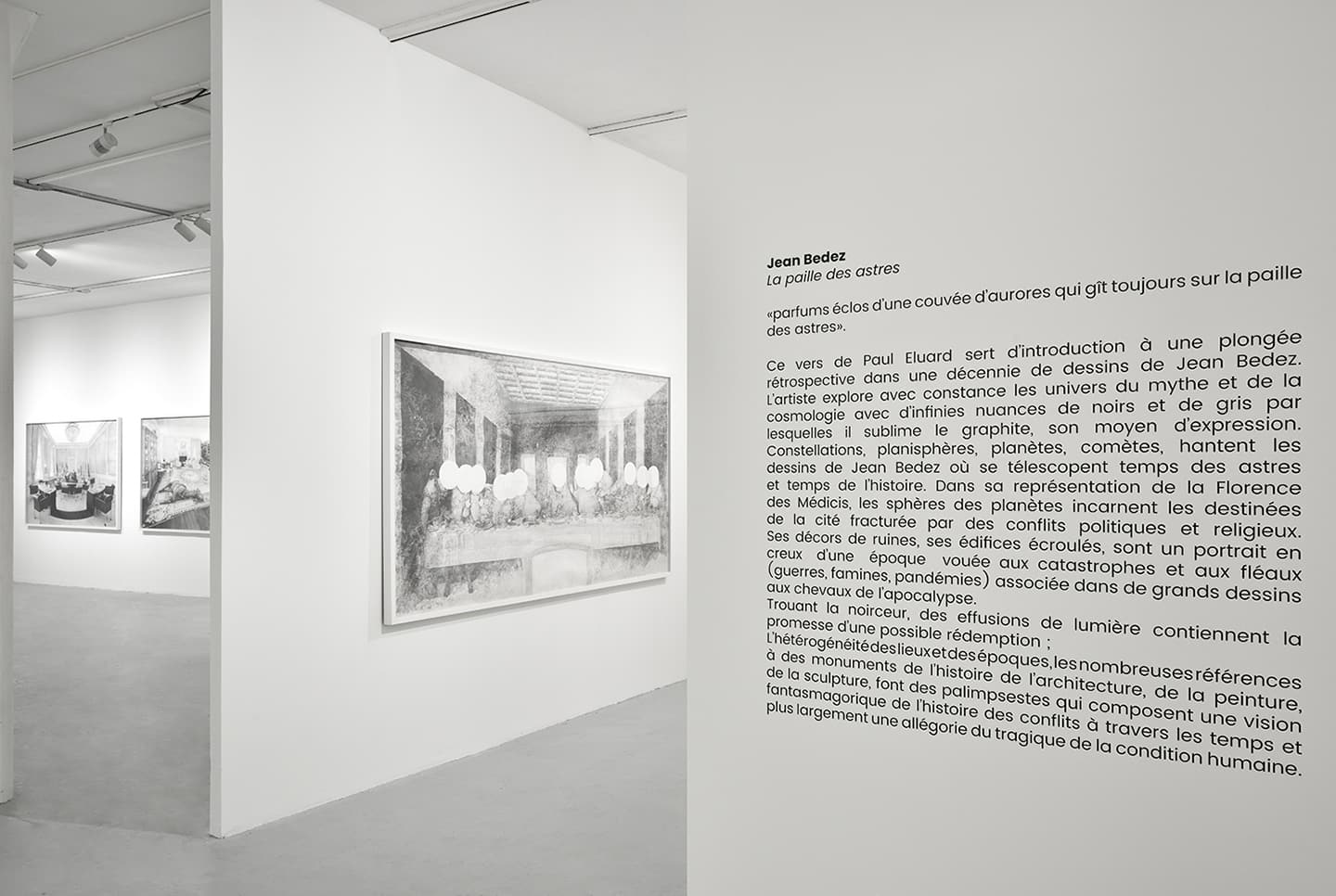

In fact, L’Art du combat is rendered through multiple openings, “with lots more mid-games, and never any endgames,” as Bedez puts it. “For example, there is another possible opening, both at the back of the exhibition and in the gallery window. It rests on two drawings inspired by works dating alike from the same year: 1498.” At the end of the sequence there is Le Cénacle, referring to the Leonardo da Vinci painting, The Last Supper. It as if we can see the Italian master’s faded colours coming through the shades of grey, the layers of graphite, and the sfumato repeating his. But the faces of the apostles have disappeared. The bright reserve of the paper forming an aura replaces them. And then, in the window, from the street, we see Saint Michael slaying the dragon. This is one of the sixteen Dürer woodcuts inspired by the Apocalypse of Saint John. Printed on towels in Egyptian cotton, these pieces closed Bedez’s 2010 exhibition at the Centre Régional d’Art Contemporain in Sète. They are “replayed” here and lead visitors into the rest of the exhibition.

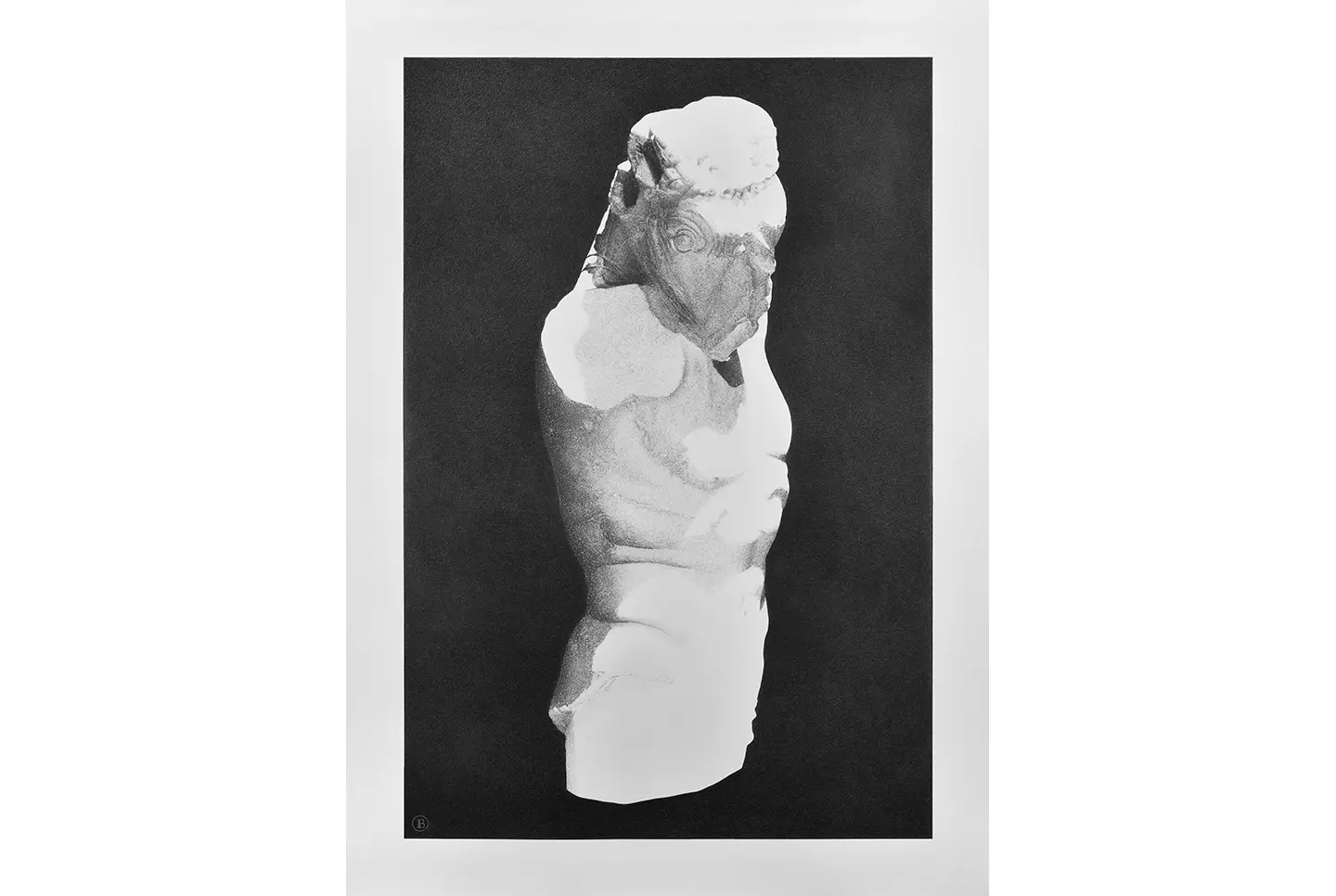

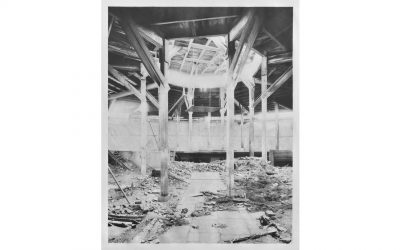

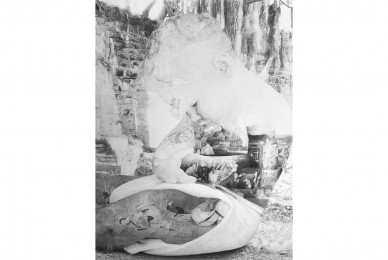

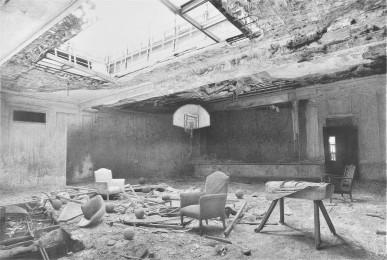

We come next to Refrigerium, a large, bright room in a state of ruin. All the light sources here have pure geometrical forms. This and the other works in the show have a performative dimension, something to do with development (révélation in French), in the photographic sense, with the images emerging through the many layers of graphite and, sometimes, through the white of the exposed paper. In a way, the work itself is making us concentrate and drawing us into a meditative state, as if joining the artist himself at work. More than the iconography, the relation to the sacred is manifested through the material and the experience of time.

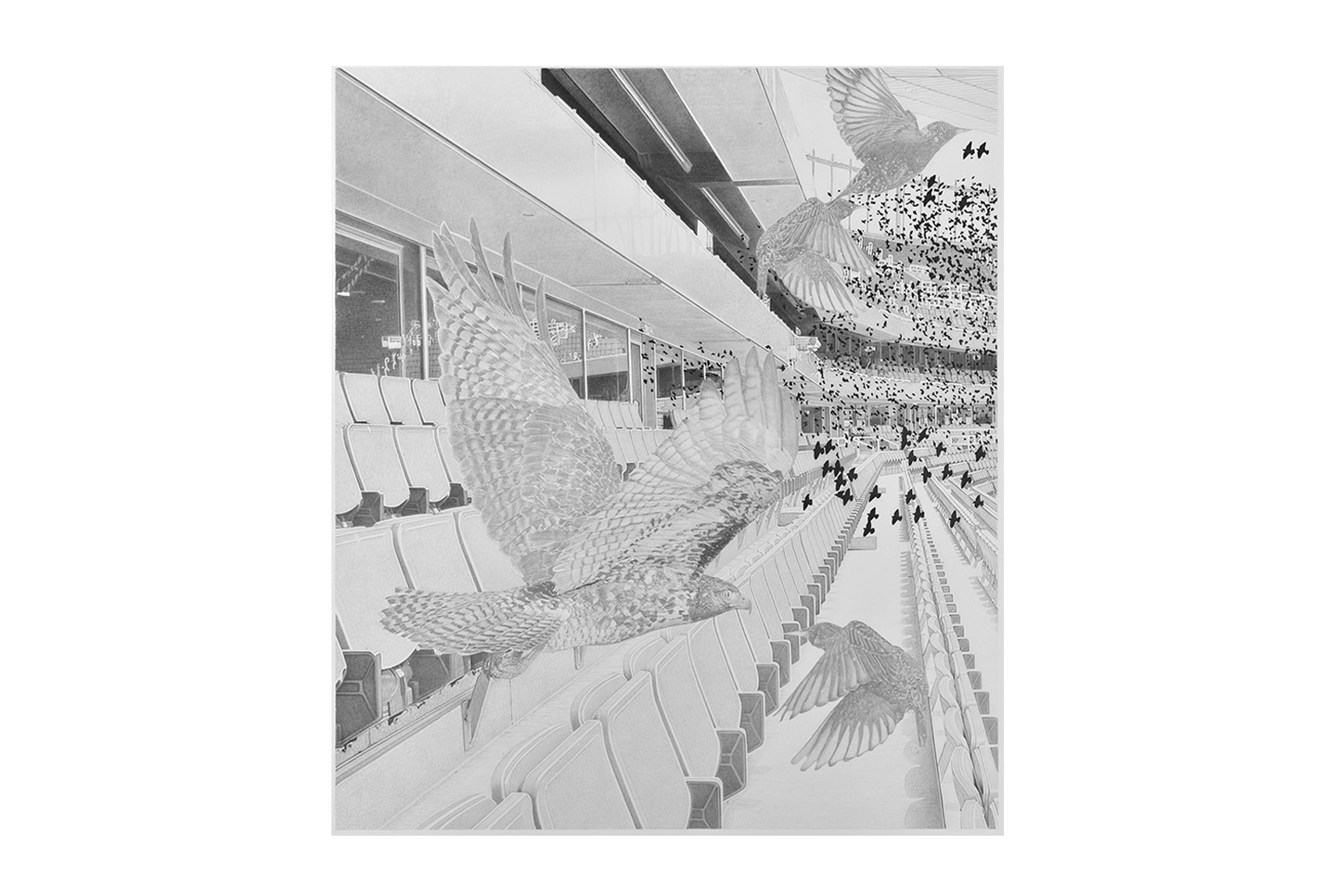

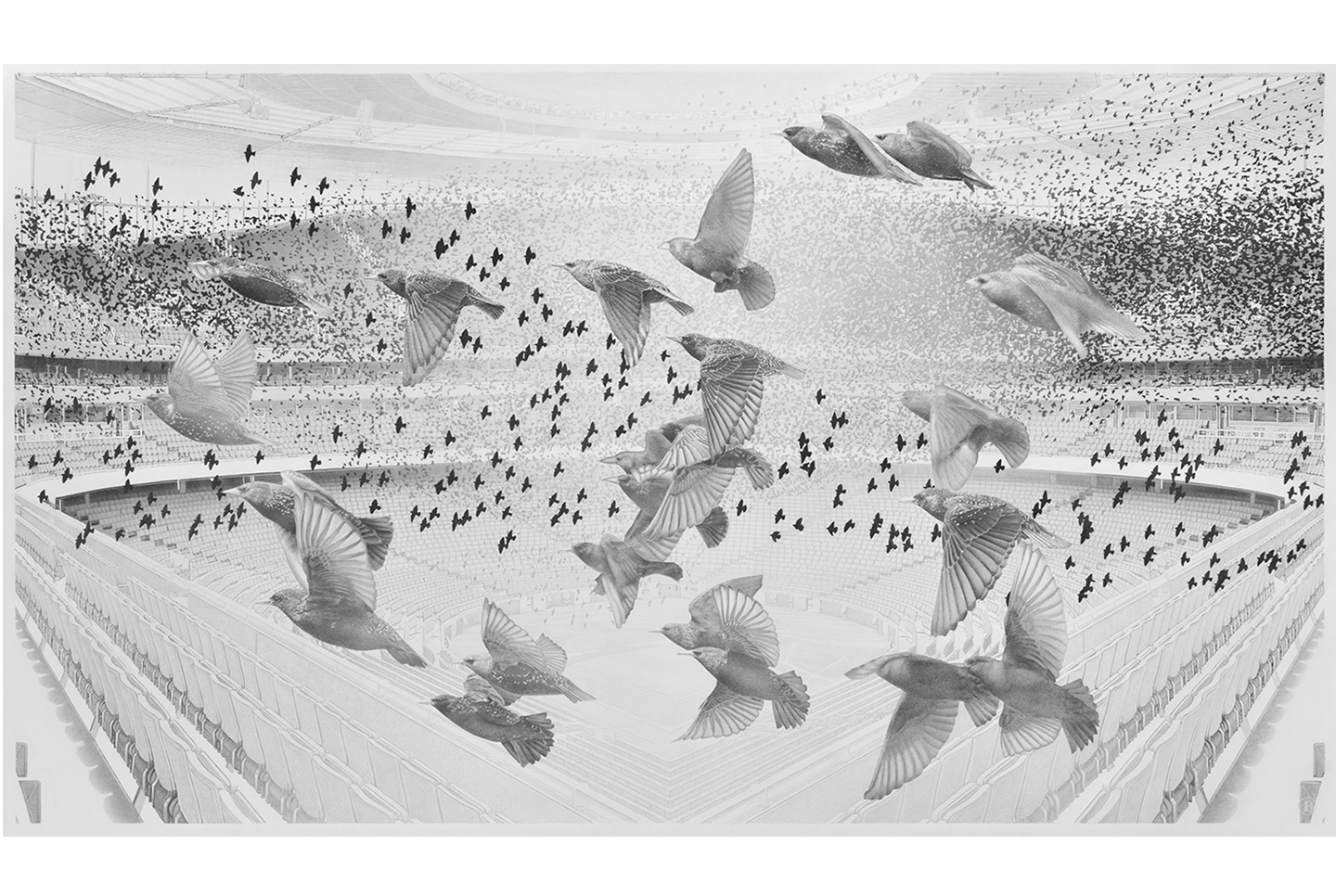

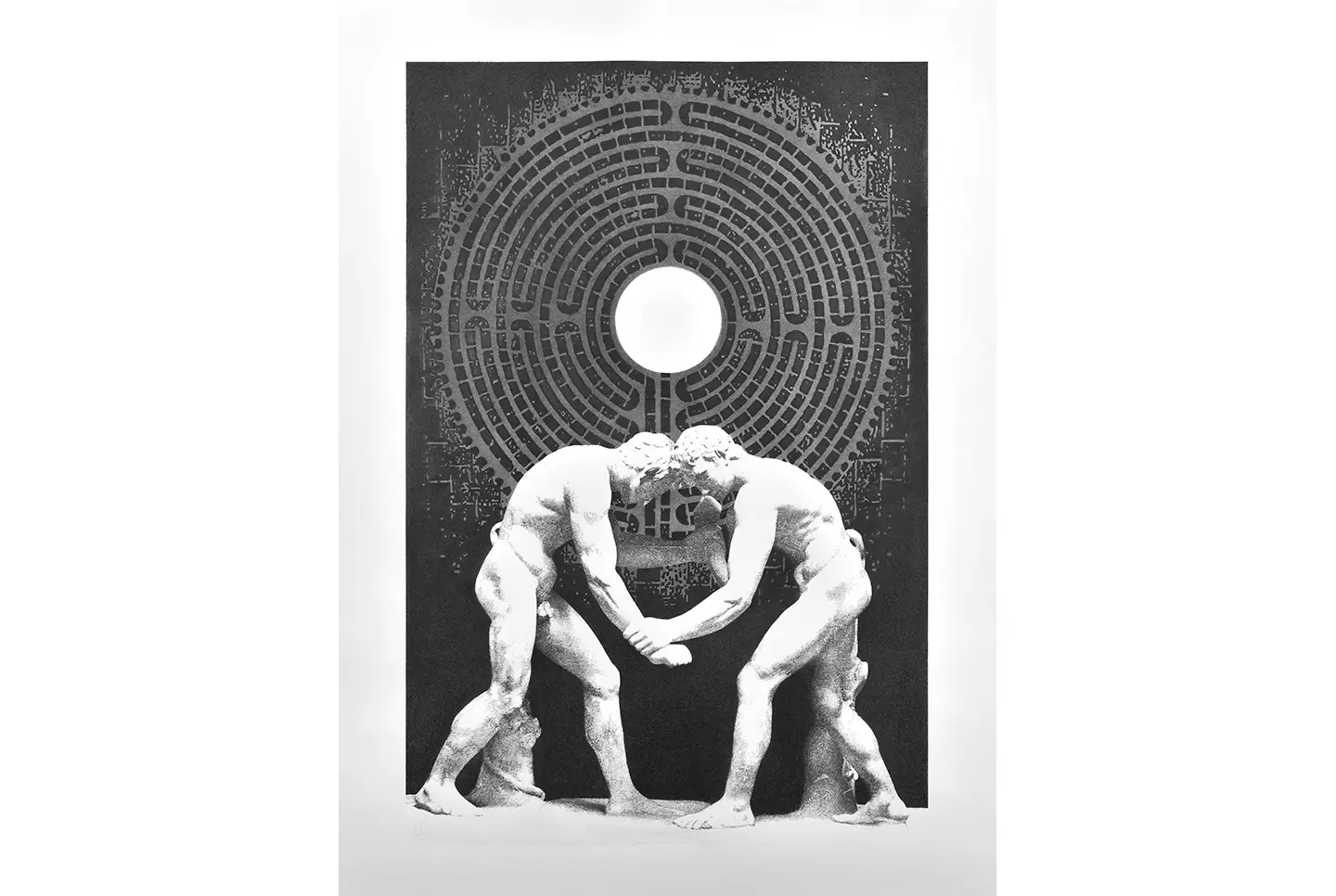

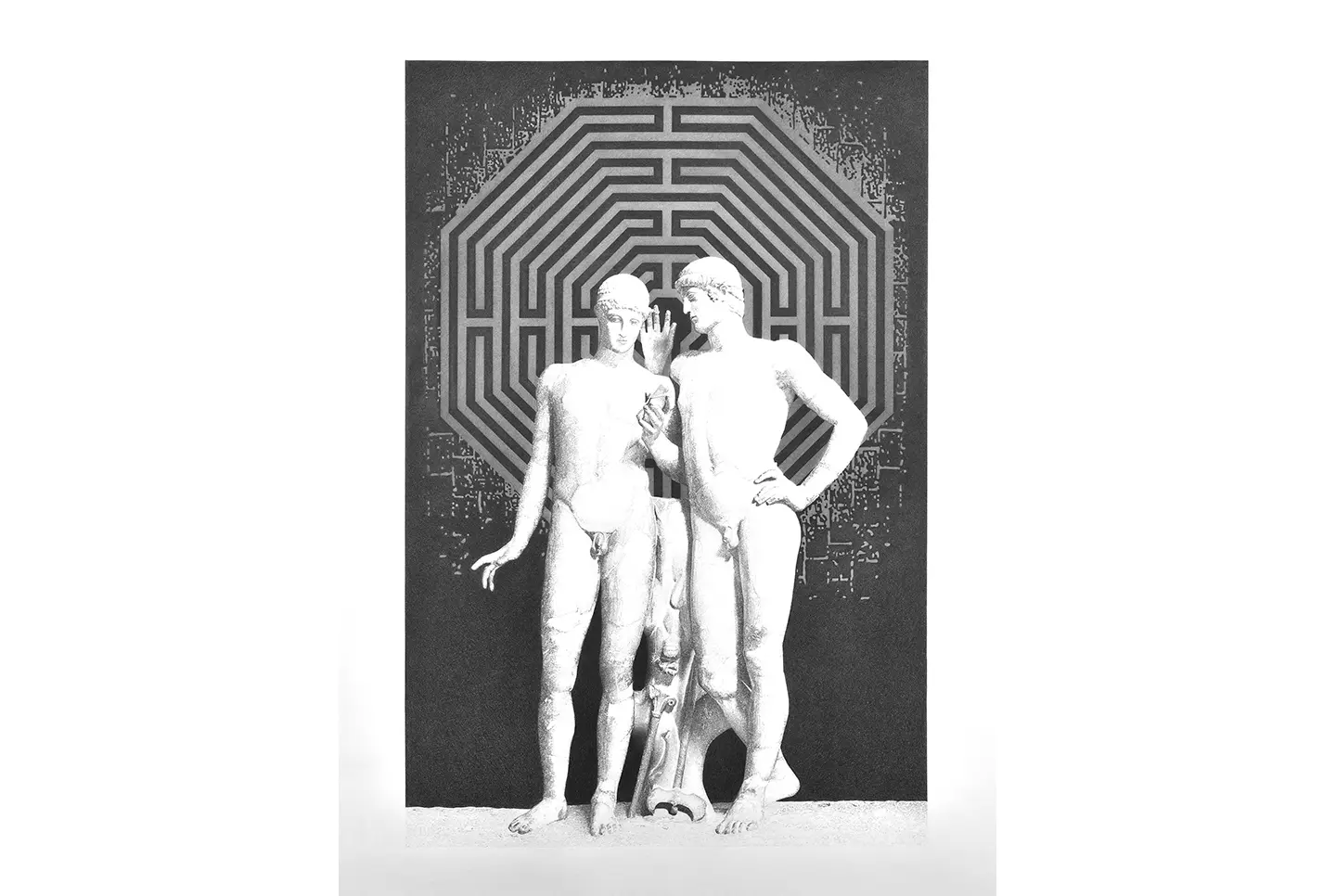

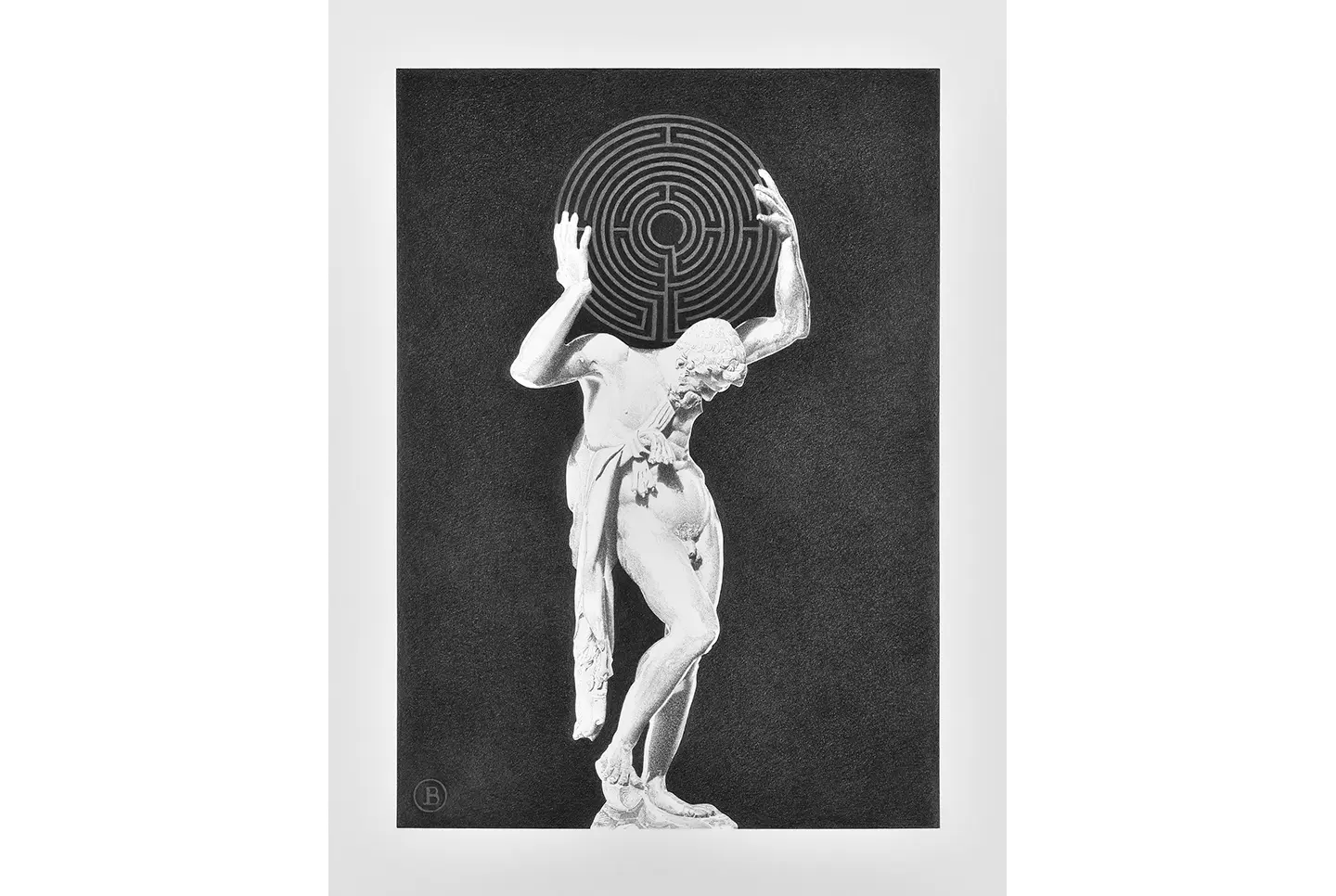

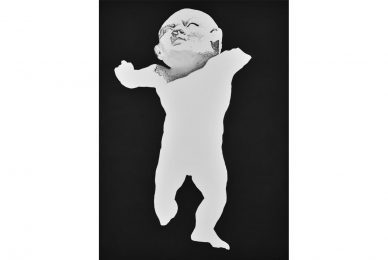

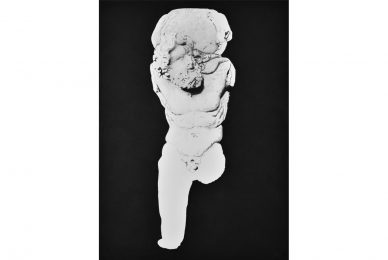

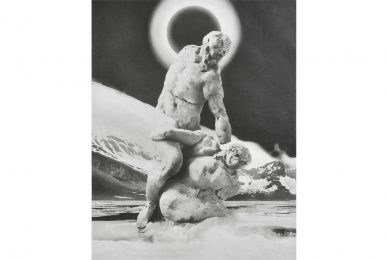

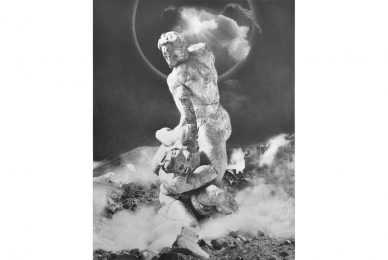

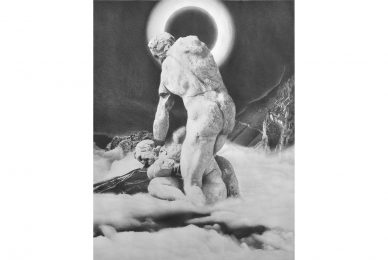

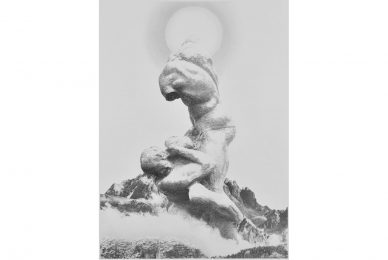

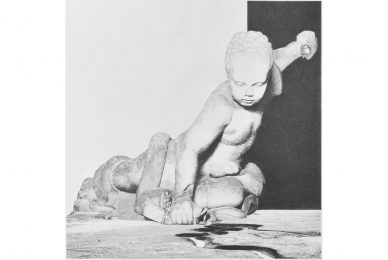

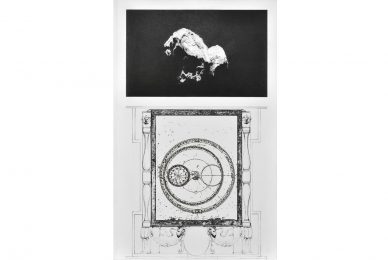

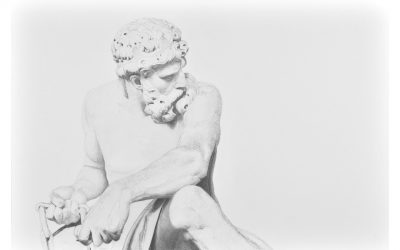

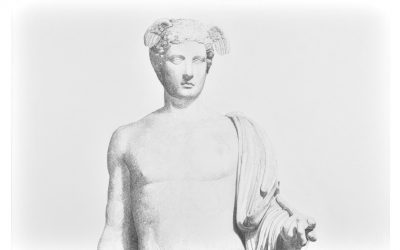

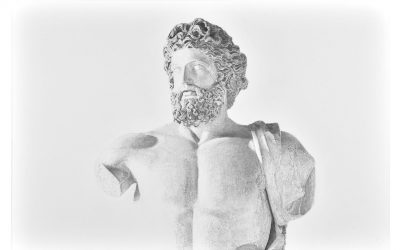

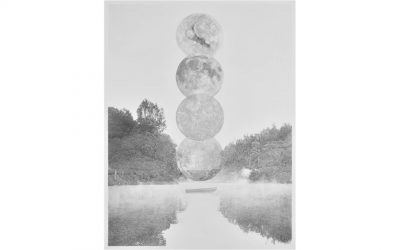

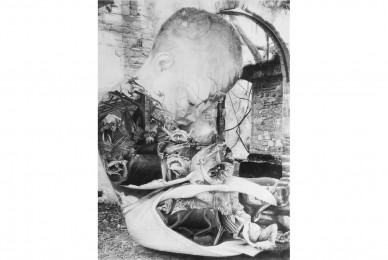

This takes us a little further on to other horsemen of the Apocalypse, each bringing the world a scourge. While these originated in the iconography of the Italian Renaissance, Bedez gives them a very contemporary twist, even more so than the Dürer prints. These four drawings which, despite their large format, we can embrace in a single gaze from the doorway, exist first of all through the artist’s four signatures, each of which symbolizes one of these drawings, making them inseparable from one another. These four horses−their riders having disappeared−lead us from the 15th century to the present day.

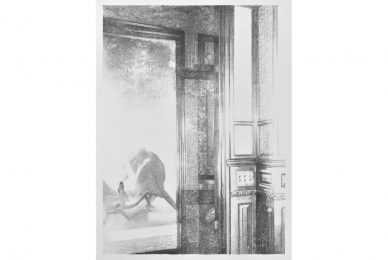

The white horse of conquest lies in the Gothic smoking parlour of a steamboat that ferried American businessmen in the oil business from Detroit to New York at the turn of the 20th century. In the background, the stained-glass image of René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle takes us back three centuries to the evangelical ardour of the first explorers trying to convert the Indians to Catholicism, while the horse, the bow and the crown seen in the signature evoke past and present wars.

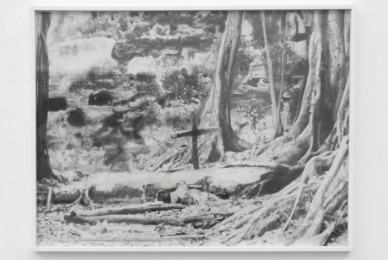

If we stay in front of this big drawing long enough, through the light we can make out a Christian cross. As Bedez points out, the centre of the picture is in exactly the same position as Christ in Le Cénacle, a little further on.

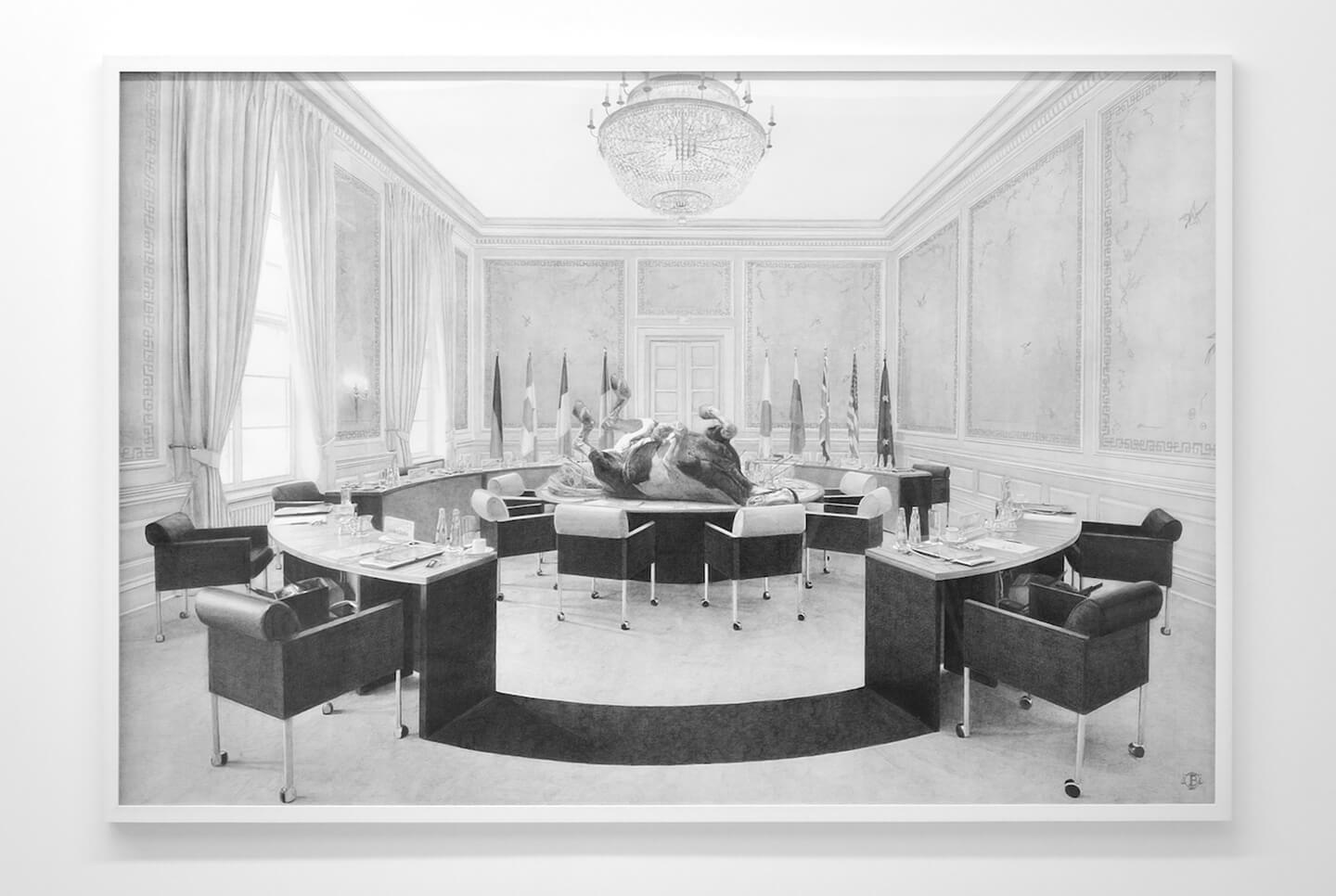

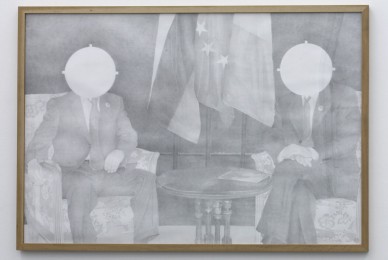

We go now from conquest to famine, via a symbolic denier (coin), the one for which Napoleon sold Louisiana, echoing the “denarius” of the apocalyptic horseman on the black steed: “A measure of wheat for a denarius and three measures of barley for a denarius; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine.” Here we are in a meeting room at the 33rd G8 summit, held in 2007 at Heiligendamm. Another place where men of power come together. But this room is empty. It would seem that the negotiations over sustainable development and aid for Africa have failed. We are on our way to the crisis of 2008.

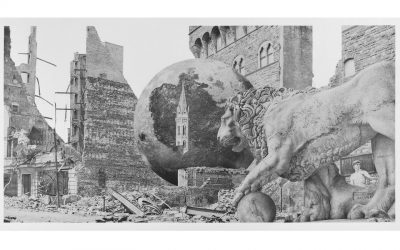

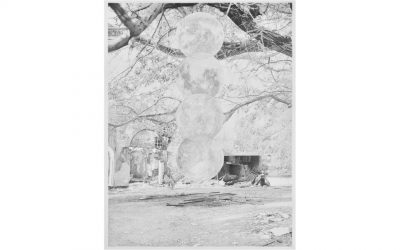

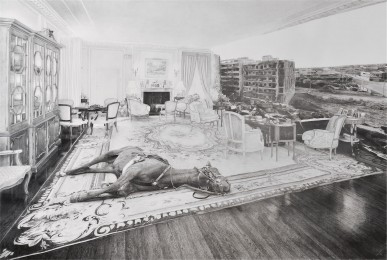

And it is from here that the scourge of civil war might arise, carried by the red horse of the Apocalypse. From the images of war-scarred Libya Bedez has erased, once again, all trace of human or other life. In the signature we recognize Napoleon’s sabres. And, on a chessboard laid on a table, the military strategies used by great historical figures. The image of a bourgeois apartment recedes into the background because of the surrounding blur, behind the horse harnessed for war in the foreground.

The last scourge is pestilence, or death. A horse is lying before the altar of Reims Cathedral, temporarily transformed into a temple of reason in the 18th century and bombed in 1944. A picture recalls the great plague in Marseille. Six artificial lights lead to the seventh, a natural one, in the choir of the church. But if Bedez is interested in religion, it is less because of the beliefs than for its relation to power, politics and spirituality.

In this game being played before us, the luminous Christ-like presence of Rouen Cathedral might refer us to the Cénacle and, from there, to the Goûteurs (Supper Eaters), where we see five people around a table, with the place setting only for the sixth, the photographer or the artist. The setting here is very different. We are in America at the turn of the 20th century. This could be a modern last supper where the diners eat segments of apple, as in the Bible. Along with the Cénacle, this is one of the few paintings in which we see human figures, even if the faces of the apostles in the latter disappear behind white disks, and even if the Goûteurs are blindfolded as if for a game of blind’s man’s buff with new rules.

Just nearby, a stairway, much of it in reserve, suggests an Ascension, but without Christ. Here we might think of the Virgin Annunciate by Antonello da Messina, raising her hand, wearing a blue veil, but with none of the usual religious signs, and with the angel only an implicit presence. Light fills all the top of the staircase, and it is perhaps this, in the permanent back and forth between the works here, that leads us to the Stabat Mater Dolorosa in the gallery entrance, which we left behind along with those chess players from 1953.

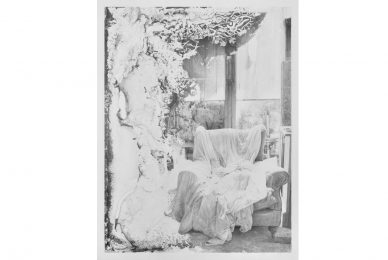

Like a small theatre model, but again a very large-format work, to the extent that we can feel ourselves entering it as we do the other large drawings, this work is graphically very accomplished. It is in part about the representation of nature, in this case in a tapestry. We see a dilapidated room with bright light flooding in, above all from the ceiling, which is literally pierced by cascading light, dividing the composition into three parts. The floor is also opening up, as if to lead us to another place for which this ruin might be the starting point.

A starting point, too, for new work by Bedez, after the four years represented by this exhibition. Several works are already finished, others are under way. Some will be “replayed” differently, just as this exhibition, too, could be replayed according to a different game plan, as Bedez himself says, continuing with the chess metaphors.

Jean Bedez joue aux échecs. C’est pourtant la première fois qu’il transforme une exposition en un grand plateau de jeu, à l’échelle de la galerie c’est à dire dans l’espace et dans le temps, ou plutôt dans plusieurs temps, celui qu’il lui a fallu pour réaliser ces dessins, celui des récits que contiennent les images, celui qu’il faut pour les regarder dans l’exposition. Celle-ci s’intitule L’Art du combat, d’après le livre du maître soviétique David Bronstein, l’Art du combat aux échecs.

Dès l’entrée, une première « ouverture » accueille le visiteur, au sens des échecs justement. Ce sont trois dessins de petit format, représentant chacun les deux mêmes joueurs face à face, comme trois instants suspendus qui nous plongent en plein suspens. Premier championnat du monde d’échecs après la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Zurich, 1953. En pleine Guerre froide, les États-Unis et la Russie s’affrontent. C’est ce que décrit David Bronstein dans son ouvrage. À partir de ce moment là, la Russie restera à la tête du tournoi pendant vingt ans. Et c’est aussi ce que nous montre Jean Bedez, à cela près qu’il a fait disparaître, dans chaque image, le plateau d’échecs en le nimbant d’une lumière irradiante, une manière pour lui d’attirer notre attention sur le dessin, sur ce temps immémorial qui se dessine à partir de cette situation historique.

Mais l’Art du combat de Jean Bedez se dessine en réalité à travers de multiples ouvertures, « encore plus de milieux de parties, et surtout jamais de fin de partie », comme il le dit lui-même. « Il y a par exemple une autre ouverture possible, à la fois au fond de l’exposition et dans la vitrine de la galerie. Elle repose sur deux dessins inspirés d’œuvres datant d’une même année : 1498. » Au bout du parcours, il y a le Cénacle qui se réfère à celui de Léonard de Vinci. A travers les nuances de gris, les couches de graphite, le sfumato qui reprend celui de Léonard, on a l’impression de voir surgir les couleurs délavées du maître italien. On dirait une radiographie. Mais les visages des apôtres ont disparu ; une aura en réserve les remplace, chacune éclairée par la blancheur du papier. Et puis dans la vitrine, de la rue, on voit Saint Michel tuant le dragon. C’est l’une des seize gravures de Dürer inspirées de l’Apocalypse de Saint Jean, qui ont été imprimées sur des draps de bain en coton d’Egypte. Ce travail, qui clôturait l’exposition de Jean Bedez au Centre régional d’art contemporain de Sète en 2010, est ici en quelque sorte « rejoué », et entraine le visiteur vers la suite de l’exposition.

C’est alors sur le Refrigerium que l’on tombe, une grande pièce en ruines et lumineuse. D’ailleurs, toutes les sources de lumières y prennent des formes géométriques pures. Il y a dans cette œuvre et dans les autres de l’exposition, une dimension performative, quelque chose qui relève de la révélation, au sens photographique de l’apparition des images à travers les nombreuses couches de graphite superposées et, parfois, à travers le blanc du papier laissé en réserve. C’est en quelque sorte l’œuvre elle-même qui nous concentre et nous absorbe dans la méditation, comme pour rejoindre celle de l’artiste au travail. Plus encore que par l’iconographie, le rapport au sacré apparaît ainsi à travers la matière et l’expérience du temps.

Par ce biais là, c’est vers d’autres cavaliers de l’Apocalypse, apportant chacun au monde un fléau, que l’on arrive un peu plus loin. S’ils trouvent bien leur origine dans les images de la Renaissance italienne, ceux-là, Jean Bedez les a rendu tout à fait contemporains, encore plus que les gravures de Dürer. Ces quatre dessins, que l’on peut un instant, sur le seuil d’une porte, englober d’un regard en dépit de leurs grands formats, existent d’abord à travers les quatre signatures de l’artiste, qui symbolisent chacun de ces dessins, et qui les rendent indissociables les uns des autres. A eux quatre, ces chevaux – car les cavaliers ont chaque fois disparu – nous conduisent du xve siècle à aujourd’hui. Le cheval blanc de la conquête se tient dans le fumoir gothique d’un bateau à vapeur sur lequel les hommes d’affaires américains voyageaient de Détroit à New York, à la recherche du pétrole, au début du xxe siècle. Au fond, le vitrail représentant René-Robert Le Cavelier de la Salle renvoie la scène trois siècles plus tôt, à la volonté qu’ont eu les premiers explorateurs de convertir les peuples amérindiens au catholicisme, tandis que le cheval, l’arc et la couronne que l’on voit dans la signature, incarnent les guerres ancestrales comme les guerres d’aujourd’hui. Et si l’on reste assez longtemps devant ce grand dessin, une croix chrétienne se dessine à travers la lumière, le centre du tableau étant, comme le souligne Jean Bedez, exactement à la place du Christ dans le Cénacle qui se trouve un peu plus loin.

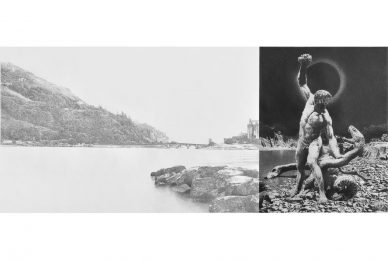

De la conquête, c’est à la famine que l’on passe, par un « denier » symbolique, celui pour lequel Napoléon a vendu la Louisiane, qui rejoint dans un écho le « denier » du cavalier du cheval noir de l’Apocalypse : « Une mesure de blé pour un denier, et trois mesures d’orge pour un denier ; mais ne fais point de mal à l’huile et au vin. » On se trouve alors dans une salle du 33e sommet du G8,

en 2007 à Heiligendamm. C’est aussi un lieu où des hommes de pouvoir se sont réunis. Mais la salle est vide, et les négociations qui avaient pour thème le développement durable et l’aide au développement en Afrique semblent avoir échoué, ouvrant la route vers la crise de 2008.

C’est de là que pourrait surgir le fléau de la guerre civile, porté par le cheval rouge de l’Apocalypse. Dans des images de la Libye en proie à de violents combats, Jean Bedez a effacé toute présence humaine et toute vie. Dans la signature, on reconnaît les sabres de Napoléon. Et dans un échiquier posé sur une table, les stratégies militaires que les grands hommes de l’histoire mettent en œuvre. L’image d’un appartement bourgeois passe au second plan par l’effet de flou qui l’entoure, derrière le cheval harnaché pour la guerre qui se trouve au premier plan.

Le dernier fléau est enfin celui de la pestilence, ou de la mort. Un cheval y repose devant l’autel de la cathédrale de Rouen, un temps transformé en temple de la raison au xviiie siècle, et bombardée en 1944. Un tableau rappelle la grande peste de Marseille. Six lumières artificielles conduisent à la septième, naturelle, dans le chœur de l’église. Mais si Jean Bedez s’intéresse à la religion, c’est moins pour la question du culte que pour son rapport au pouvoir, au politique, à la spiritualité.

Dans cette partie en train de se jouer, la présence christique lumineuse de la cathédrale de Rouen pourrait nous renvoyer au Cénacle et, de là, aux Goûteurs, où l’on voit cinq personnages attablés, avec seulement les couverts du sixième, le photographe ou bien l’artiste. Le décor est ici tout autre, et se situe au début du xxe siècle en Amérique. Cela pourrait être un dernier souper contemporain, où les dîneurs mangent des quartiers de pomme comme dans la Bible. C’est avec le Cénacle l’un des seuls tableaux où l’on voit des hommes – même si les apôtres du Cénacle ont le visage couvert d’un disque blanc, et si les Goûteurs ont les yeux bandés, comme dans un jeu de colin-maillard dont on aurait changé les règles.

Juste à côté, un escalier, laissé pour une grande part en réserve, évoque l’image d’une Ascension, mais sans le Christ. On pourrait penser à l’Annunciata d’Antonello de Messine, qui lève la main, sous son voile bleu dépourvu de signes religieux, une Annonciation dont l’ange se trouve aussi en hors champ. Sur l’escalier, la lumière occupe tout le haut de l’image, et c’est peut-être elle, dans ce permanent va et vient entre les œuvres, qui nous ramène au Stabat Mater Dolorosa, dans l’entrée de la galerie, que nous avions laissé à côté des joueurs d’échecs, en 1953.

Comme une petite maquette de théâtre, mais là aussi en très grand format, si bien que l’on peut s’y sentir entrer tout entier comme dans les autres grands dessins, cette œuvre est graphiquement très aboutie. Il y est question de représentation de la nature – ici sur une tapisserie. On y voit une pièce en ruines, elle aussi entourée d’un éclat qui provient de toute part, et surtout du plafond qui est littéralement transpercé par une cascade de lumière – laquelle divise la composition en trois parties. Le sol, transpercé lui aussi, nous conduit encore vers un ailleurs dont ces ruines sont le commencement.

Un commencement vers la suite du travail de Jean Bedez, après quatre années de travail montrées dans cette exposition. Plusieurs œuvres sont déjà achevées, d’autres sont en cours. Certaines seront « rejouées » autrement, de même que l’on pourrait « rejouer » cette exposition selon une partie un

peu différente, comme Jean Bedez le dit lui-même, en filant toujours cette métaphore du jeu d’échecs.